Student Information

Part 1: Program Expectations

This program offers a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA). We focus on personal vision and critical inquiry over commercial templates.

1. Technical Skill vs. Artistic Agency

We are moving from being "executors" of styles to "authors" of visual languages.

Body Representation: We will avoid "mimetic" bodies. Unlearn "Pixar eyes" or "anime proportions" in favor of observation.

Type your full name to acknowledge these goals:

Part 2: Visual Conditioning Worksheet

Two Visual Languages

.jpg)

Dave Greco, character design

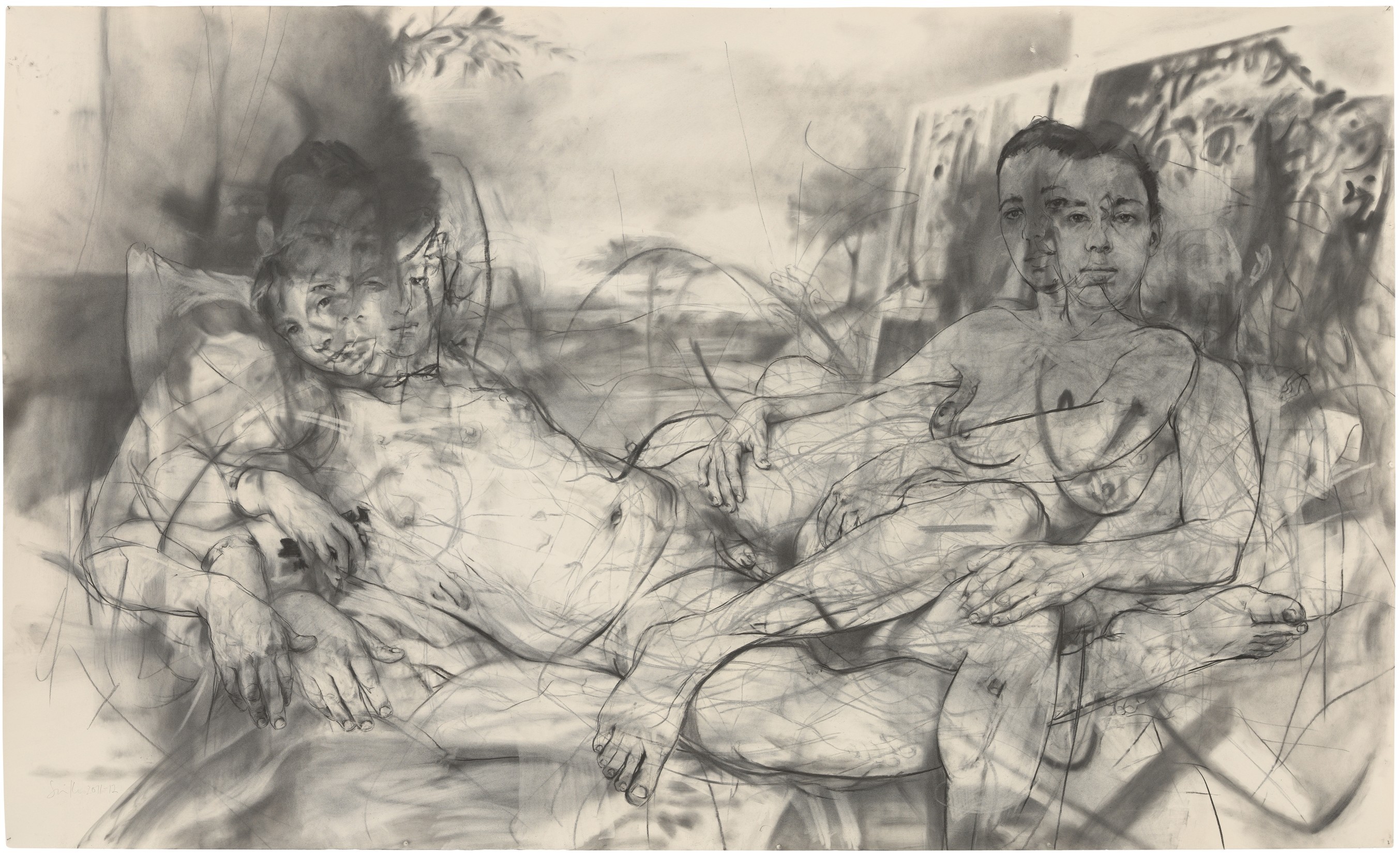

Jenny Saville, "Mirror"

How have you drawn bodies in the past? What rules were you trying to meet?

Transformation: Joyce Pensato

What choices make Pensato's version her own? How is it different from fan art?

Drawing Activity: Transformation

Create 3 drawings transforming a character completely, expressing raw emotion through material struggle.

Your Perspective

Respond to the analysis of fan art, ownership, and definitions of art.

Submission Instructions

- Click the floating SAVE PROGRESS button to download your completed worksheet.

- Create a folder:

LastName_FirstName_VisualLanguage - Place the downloaded file and your 3 drawings inside.

- Zip the folder and upload to Canvas.